Britain’s power grid has repeatedly fallen below its targeted frequency level this year, raising fears that it is struggling to cope with intermittent energy supplies.

It comes amid rising international energy costs and a recent drop in wind power due to particularly still weather. Earlier this week the UK was forced to bring a coal-fired power plant back online to boost the grid.

The grid’s level of frequency dipped to between 49.79Hz and 49.67Hz on 11 occasions between February and June, according to data analysed by The Sunday Telegraph from the Gridwatch database which measures frequency at five-minute intervals.

This is within the legal limit of 49.5Hz but outside what National Grid sets as its own operational limits of between 49.8Hz and 50.2Hz.

Frequency is determined by the balance between power supply and demand, which needs to be continuously matched. The British grid is set to run at 50Hz.

There were national blackouts in August 2019 when a wind farm and gas-fired power plant tripped off, triggering a plunge in frequency to 48.88Hz and other local generators to disconnect. Generators are set to trip if the frequency falls too fast, to avoid damage.

National Grid said it “operates one of the most reliable electricity systems in the world, and frequency deviations outside our required limits are extremely rare”.

Matching power supply and demand can be more challenging when there are more intermittent sources of power on the system, such as wind and solar plants. These green sources of energy also lack the ability of fossil fuel generators such as coal and gas-fired plants to help stabilise the grid even if the generator has tripped, by providing inertia.

Renewable power generated more electricity than fossil fuels in the UK in 2020 for the first time. During the year, 43.1pc of UK power came from renewables and 37.7pc from fossil fuels, with nuclear and imports making up the bulk of the rest. Britain now goes for long stretches without using domestic coal-fired power stations, and officials want to be able to run the grid without gas-fired generation for short periods by 2025.

National Grid ESO, which balances Britain’s electricity supply and demand, has introduced new techniques to help it manage frequency even as the power system evolves, including technology to respond more quickly to frequency changes, and making generators less sensitive to falls in frequency.

Tom Edwards, at Cornwall Insight, said giant power cables connecting the British power grid to the Continent are a growing cause of frequency changes.

The power cut in August 2019 was the first in a decade in Britain, affecting more than a million people as well as hospitals, airports, rail and road networks, from the South East to Yorkshire.

Hornsea One, RWE and UK Power Networks were fined £10.5m in total by Ofgem. National Grid was not censured but Ofgem has since recommended that its role balancing supply and demand be handed to an independent body.

The Nemo subsea cable to Belgium carries electricity to a plant in Kent where power is fed into the grid.

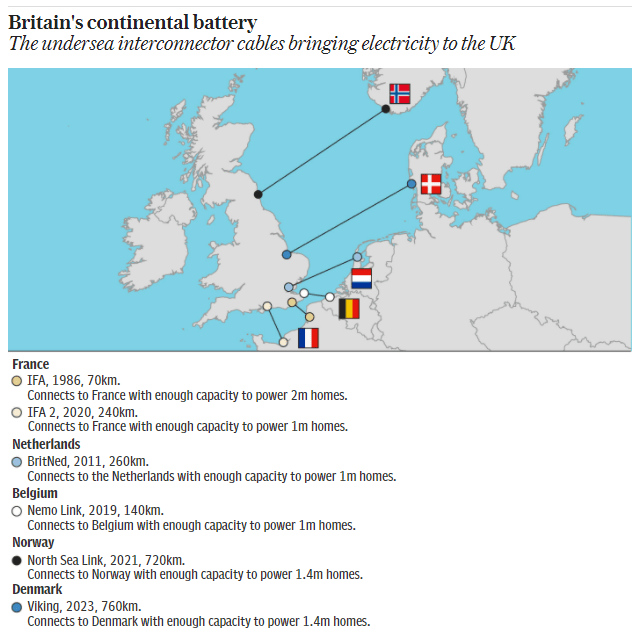

As Britain battled record electricity prices last week, power continued to flow along the 720km new cable between Blyth in Northumberland and Kvilldal in south-east Norway.

Officials were testing the North Sea Link that plugs Britain into Norway’s hydropower-rich electricity system, which should be able to supply up to 4.2pc of the UK’s electricity demand once fully up and running in October.

It is among a growing number of giant underground power cables – known as interconnectors – between Britain and continental Europe, including a planned first-ever link with Germany which developers hope to start using by the mid-2020s.

Officials on both sides are counting on such cables to play a key role in the energy system as the industry shifts towards renewables, helping to smooth out gaps in supply and demand from intermittent wind and solar power.

The system means new ties with Europe – setting up opportunities for the country to make the most out of its vast offshore wind resources, yet also forming a new energy dependence in the renewable era.

“Electricity generation is moving away from localised generation to generating in the most geographically optimal way,” says Hugo Lidbetter, partner at Fieldfisher law firm.

“In the North Sea, that’s offshore wind; in southern Europe, it’s solar. Interconnection is one way of moving that power around to balance the markets.”

Britain had its first power links to the Continent in 1961. Now there are six connected to the Irish single electricity market, France, the Netherlands and Belgium. Those cables supplied about 8pc of Britain’s power last year and several more are in development, including to Norway, France, the Netherlands. Another, the NeuConnect project to Germany, is backed by investors including Meridiam, Allianz Group and Japanese utility Kansai Electric Power.

National Grid says projects are in place that will be able to supply 25pc of British power by 2024, while links further afield than Europe are also being looked at. Entrepreneurs led by Simon Morrish are exploring plans to build a cable bringing power from Morocco’s sun-drenched Sahara all the way to Britain.

This Xlinks project echoes an aborted plan in the early 2000s known as Desertec, which aimed to create giant wind and solar parks in North Africa before ultimately failing amid political and practical concerns.

In the current state British interconnectors are mostly used for importing cheaper power than is provided by domestic generators. Officials, however, expect Britain to become a net exporter of power by 2040 at the latest as its offshore wind capacity grows.

Confirmed projects so far mean that British interconnector capacity is set to expand from about 4GW to 13GW by the end of the decade. That is still less than the 18GW the Government has said it wants in place by 2030 to coincide with the planned fourfold ramp up in offshore wind power.

Projects are expensive, lengthy and complicated – though it remains an attractive investment area. Humza Malik, chief executive of Frontier Power, which is behind the Zeno interconnector project to the Netherlands and active on other developments including NeuConnect, is positive. He says the cap and floor regime introduced by Britain’s regulator Ofgem has provided “a level of certainty for investors without exposing consumers to unacceptably high prices.”

Industry was spooked, however, at the end of 2020 by the threat of access to the EU’s single energy markets becoming a political tool amid Britain’s departure from the EU. The bloc’s chief negotiator Michel Barnier reportedly threatened to block Britain from the market in an effort to attract concessions on fishing rights, while France’s President Emmanuel Macron wielded a similar threat.

Both fishing rights and energy market access are up for renegotiation in 2026, raising the prospect of the threat rearing its head again. John Pettigrew, chief executive of National Grid, has tried to pour cold water on those concerns, telling the Financial Times in July that there has “never been much tension around the interconnectors” as they are seen as “of mutual benefit”.

Brexit has, however, restricted access to EU development funding. Experts say it might also cut incentives for European countries to develop interconnectors with Britain now it is outside the EU’s own targets for interconnection.

Regulators may think “if there’s no benefit for my consumers, and the only benefits are for British consumers, why should I bother?” says Tom Edwards at energy research firm Cornwall Insight. “There’s less quid pro quo.”

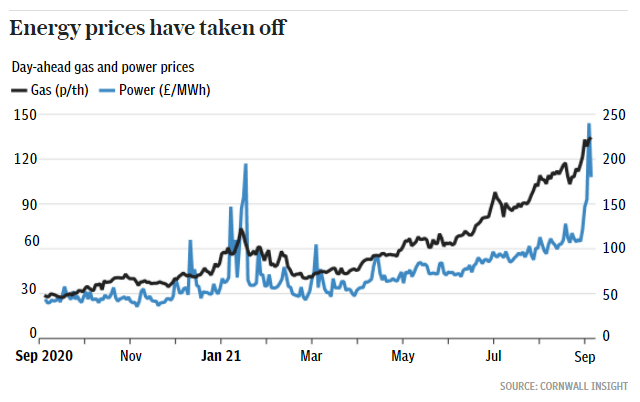

Electricity prices between interconnecting markets do tend to converge and, currently, British power is typically more expensive than in Europe partly due to top-up prices on carbon in Britain. Cornwall Insight points to studies suggesting the North Sea Link between Britain and Norway will raise Norwegian power prices by between £1.7 – £2.1 per MWh, while reducing prices in Britain.

The soaring prices in British and EU power markets last week provided a window into the opportunity for interconnectors – but also the risks. A global gas supply crunch and lull in wind power pushed power prices in Britain to all time highs of £285 per MwH on Thursday – more than four-times their normal rate.

Many argue the chaos highlights the need for more flexibility in the system to help smooth out renewable energy supply and spiking gas prices. This can be provided by interconnectors and other sources such as car batteries plugged into the grid, storage batteries, hydropower and hydrogen.

The large risks were also made clear as Ireland blocked power exports to Britain via the Moyle interconnector that links Northern Ireland and Scotland. It followed warnings of generation shortfalls in the Irish market, where it is believed the rise of power-hungry data centres are putting extra strain on the grid.

Glenn Rickson, head of European power analysis at S&P Platts, says diversifying sources is important. “There will always be times of relatively tight supply. Britain struggles the most when wind generation is low. It tends to be the case that if wind is low in Britain it’s also low in the rest of Europe.

“It helps that we are diversifying connection points to other countries, spreading around the risk of low wind supply and other factors.

“But you need to build flexibility: interconnection is a tool in the armory, but you need other solutions as well.”

The Nuclear Industry Association trade body, which published the analysis of National Grid’s record spending, insists that stable nuclear power is what is needed instead.

“The key electricity market in Europe is Germany,” he says. “It sits in the middle and consumes a lot. And Germany start aggressively shutting their coal and nuclear power next winter, which might start driving prices higher in Europe.”

Ireland’s decision to block power exports might not end up being an isolated event.

“Europe has a single electricity market and generally power flows from the cheapest to most expensive markets. There are also the laws of physics which means that power doesn’t stop at borders,” said Rickson.

“Under competition law there are rules against “hoarding” power by one country but when security of supply is at risk there are precedents for countries preventing exports to neighbouring markets where possible, and it’s not inconceivable we could see that happen again this winter in extreme circumstances.”

Original Article – https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2021/09/11/power-struggle-europe-uk-grid-struggles-keep-lights/